Image by NASA

If you are like me, you've spent a great deal of time during the pandemic revisiting in your mind's eye some of the most fascinating places on this earth that you visited before the freedom to travel was taken from us by the coronavirus.

We shared with you a brief glimpse at one such place in the July/August 2019 feature, B&B'ing Through Canada's Maritime Provinces. Now we'd like to take a closer look.

During our sojourn through Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and New Brunswick, we took a short side trip to France - but we didn't cross the Atlantic Ocean to the European Continent. No, we took a ninety-minute ferry ride to a tiny outpost of French sovereignty.

The archipelago known officially as Collectivite Territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon is the last remaining fragment of what was once France's three million square mile North American territory that reached from New Orleans to Hudson Bay.

Now, fewer than one hundred square miles of that territory remain French.

The image above is a 3D construction by NASA showing the major islands of SP-M. The island at the bottom is Saint-Pierre, site of the capital town where all but about 600 of the just over 5,000 people in the territory live. That capital is also called Saint-Pierre, in honor of Saint Peter, the patron saint of fishermen.

The three connected islands at the top are collectively Miquilon, a Basque form of the name Michael. These islands used to be separate, but wind and wave have deposited sand on shoals between them which have grown into what geologists call tombolos. Today you can even drive from one to the other.

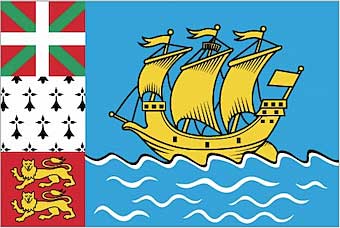

The flag of this "collectivity" tells the story of its history.

The flag of the Collectivite Territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon

Closest to the flag pole is a column of three heraldic marks - those of Brittany, Normandy and the Basque country that spanned portions of what is today southern France and northern Spain. These were the territories from which the first French settlers came to exploit the fishing opportunities presented by the cod that swarmed nearby.

The two-thirds of the flag farthest from the flag pole shows a three-masted sailing ship on stylized waves. This represents the ship Grand Hermine (or Hermione depending on what you read) commanded by Jaques Cartier when he claimed the archipelago for France in 1536.

Cartier wasn't the first European explorer to visit - and claim - this land. The first was a Portuguese sailor named Joao Alvarez Faguendez, who in 1520, came up with the fantastic name: "The Islands of Eleven Thousand Virgins." There doesn't happen to be any indication that there were any humans inhabiting these islands at the time, let alone eleven thousand - whether virginal or not. He chose the name in honor of a Saint Ursula. According to legend, she had commanded a contingent of that many virgins in medieval France. Columbus honored the same saint when he named the Virgin Islands in the Caribbean.

Our first glimpse of land

Our first glimpse of the islands may not have been too different than that of either Faguendez or Cartier, as the low-lying, rocky land without trees but with lush green scrub and peat showed little sign of habitation. As we drew closer, we spotted a few isolated buildings - apparently houses and barns.

A few buildings came into view

We rounded Cap(e) Rouge and entered the channel between the island of Saint-Pierre itself and the smaller, currently uninhabited island of L'lle-aux-Marins. It is known locally as the "Ghost Island" because its entire permanent population relocated into the town of Saint-Pierre by 1965 and now only a few take a ferry over to operate a power plant during the day.

Finally, the town of Saint-Pierre revealed itself to be a charming, colorful community which welcomes visitors with open arms.

The town viewed from a hill over the old airport

We were extremely fortunate to arrive during a spell of clear weather. None other than the British Captain James Cook, who explored these waters in the 1760s, left the comment that these islands have "three seasons: July, August and Winter." Winter hadn't yet begun when we arrived in very early September.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The ferry runs from Fortune, Newfoundland, to Saint-Pierre |

|

The interior of the ferry

|

|

It was a modern ferry we debarked from to explore the town. Our first stop was our hotel, the Hotel Robert which played an important part in one of the archipelago's most dramatic periods of history. It seems that the boom times of the 1880s and 1890s had come to a depressing end as the numbers of cod declined due to overfishing. The decision of the United States to adopt prohibition gave this tiny French outpost a new and lucrative lease on life - rum-running.

Because it was French soil, no initial crime was committed if alcoholic beverages were imported from Europe. But then, when transshipped - or smuggled - into the United States - now that's another story. Millions of bottles of wine, brandy, whiskey, gin and vodka made the trip across the Atlantic legally only to be smuggled illegally into the "dry" United States of America. Saint-Pierre imposed a minor duty of about four cents per bottle, raking in a huge windfall. This duty was a mere fraction of the forty cents per bottle duty the British imposed on shipments into the Bahamas where Nassau became the southern route for "hooch."

Gangster interests blossomed in both ports and none other than Al Capone made supervisory visits to Saint-Pierre to oversee the work of his team here. While in town, he stayed at the Hotel Robert where we were to stay the night.

The Hotel Robert where Al Capone - and we - stayed

Take a close look at that photo of the Hotel. Note the steps up from street level to the ground floor entrances. You'll find the same at entrances to most of the houses and stores in the town because, after the July and August that Captain Cook praised, the winter brings lots of ice and deep snow.

We got to our room and checked the view of the harbor out our window.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Our room on the second floor of the Hotel Robert |

|

The view out our window

|

|

Then it was off to explore. The first thing we noticed was the color in the residential areas. Many of the houses were painted in bright pastels and primary colors.

The colorful houses of Saint-Pierre |

Storefronts were often equally colorful. Here, for example, is one that faces on Place du General de Gaulle which was, of course, named for the leader of the Free French Forces during World War II who went on to lead the nation as its President.

One of the colorful storefronts facing on Place du General de Gaulle

In the late 1950s de Gaulle offered France's colonies and possessions their independence, but Saint-Pierre declined, preferring to remain part of France. This was probably in recognition of the fact that the archipelago's economy was never going to be self-sufficient and would require a subsidy from the French government for a long time.

Once fishing, especially for cod, was the life-blood of the archipelago, but today it approaches a negligible portion of the economy. The latest estimate in the CIA's World Factbook shows only 2% of the gross domestic product comes from agriculture and that fish are only one of the products in this category, along with vegetables, poultry, cattle, sheep and pigs. It attributes the decline in part to disputes with Canada over fish quotas and a decline in the number of ships stopping in Saint-Pierre. But the shore of the harbor retains some feel for the nautical past with boats pulled up on shore by colorful, red-painted winches.

A colorful winch used to haul a fishing boat out of the water

But not all the color came from residences, storefronts or winches. Some impressive modern architecture could be found along the harbor-front and each had its own story.

The Francoforum where students study French as a second language

Take, for example, the Francoforum, home of the Institut du Langue Francaise which hosts non-French speakers who come to spend a summer immersed in the local language. It is a way to spread the presence of the French national language throughout the world.

The museum offers, among other artifacts,

the only guillotine ever used for an execution in North America.

Inside the L'Arche Musee et Archives (translated: The Ark Museum and Archives) is something you can't see in any other spot in North America. It dates from 1888 when a murderer was condemned to death here. There was just one problem: Under French law of the time, the execution had to be by guillotine and there wasn't one to be had. They had to import one - an old and not-too-sharp contraption that might have been what W.S. Gilbert had in mind when he wrote in the Mikado of "a cheap and chippy chopper." The execution was botched, with the neck not completely severed and blood splattering the executioner, the victim and some bystanders. There never was another execution by guillotine in North America.

The Centre Culturel et Sportif, home of Saint-Pierre futsal

The Centre Culturel et Sportif is an indoor stadium which gets most of its use from the sport of futsal - a variant of what we in the US call soccer but the rest of the world calls football. Unlike the better-known sport, futsal is played on a hard surface on a field, smaller than even a US football field, with only five players on each team at a time. There is also a regulation soccer competition played outdoors among the three teams on the islands, but the long harsh winters here foster this indoor sport.

Saint-Pierre's airport now offers flights to/from Paris again

Yes, you can fly into and out of Saint-Pierre - on Air Saint-Pierre. Indeed, the airport here is the second field to serve the islands but the old one, nearer downtown, was abandoned in 1999 when this new one, with International Civil Aviation Organization's airport identification code LFVP opened. It is the only airport in the Americas with a code beginning with "L" which is used for European nations including France. The airline's once-weekly service to and from Paris on a 737-700 was interrupted by the pandemic but resumed operation in June.

Saint-Pierre honors its dead from both world wars

On a hill overlooking the harbor stands a veteran's memorial officially termed a monument to the dead from both world wars. Saint-Pierre and Miquelon sent nearly 500 soldiers to the French armed forces for each war. Around 100 didn't come back from the first war. The mortality in the second war was quite a bit less. Because their participation was on the side of the Free French movement of General Charles de Gaulle rather than the Vichy regime which was subservient to the Nazis, they weren't involved in combat after the 1940 armistice between Vichy and Berlin.

The harbor these statues face, however, did see some action in World War II - half an hour's worth to be precise. On Christmas Eve of 1941 a submarine and five 200 ft. long surface warships called Corvettes in service to De Gaulle's Free French entered the harbor and tied up at the wharf to be greeted by most of the local population. They took the Vichy regime's "administrator" prisoner and kept the archipelago from becoming a base for Nazi operations.

There was a brief furor over the incident but the controversy was over in less than a month. Winston Churchill wrote to Franklin Roosevelt in January, 1941 that the islands could then "relapse into the obscurity from which they have more than once emerged."

But with all the changes through history for this archipelago, the atmosphere remains that of a fishing village.

Saint-Pierre retains the feeling of a fishing village

With the hope that the coronavirus may permit us to return to actual travel adventures abroad, we would be pleased to return to Saint-Pierre - but probably not in winter.

| |

Brad Hathaway retired to live with his wife on a houseboat in Sausalito, California, after nearly two decades covering theater in Washington, D.C., on Broadway, and nationwide. He is the vice-chair of the American Theatre Critics Association’s Executive Committee. |

|

|

|

|